Frida Kahlo, Henry Ford Hospital, 1932, oil on metal panel, Museo Dolores Olmedo Patino Mexico

A year ago this week, Poland’s near-total ban of abortion prompted some of the largest protests in the country’s recent history, and it has since led to the death of at least one woman from a dangerous pregnancy that would previously have been terminated for medical reasons. Apart from its fatal consequences, the law is shocking because it goes beyond a woman’s ‘right to choose’ versus the ‘right to life’. By banning abortion for foetal anomaly, Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal is interfering in medical decisions that should be left to a woman, in consultation with her medical provider. It has resulted in the marginalisation of the women’s rights organisations and feminist movement, and those sharing a need to voice claims to equal citizenship. Sadly, this is not new in history. To understand the implications more fully, and frankly discern the antiquated notions of womanhood at play, one need only turn to two feminist works of art that shine a light on this very theme. These include Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #216 (1989), which is a subversive commentary on an Old Master painting by Jean Fouquet (1452), and Frida Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital (1932). In the wake of developments in feminist art theory in the early 1970s, many artists began to create work that dealt with the female experience and looked towards challenging the systems in place through activism.

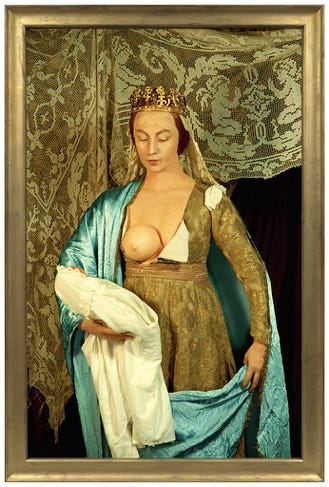

Cindy Sherman,Untitled #216, 1989, chromogenic colour print, 87x56 in., The Broad, Los Angeles

Anti-abortion legislation testifies to a patriarchy’s grip on women’s sexuality and their bodies. As a consequence, Poland faces a hardening of exclusionary policies towards women. It presents a case in which gender orders must be questioned and challenged from below. In this respect, feminist art could, and still can, have the power to influence cultural attitudes and transform stereotypes. Between 1989-1990, American photographer and film director Cindy Sherman made a series of images of biblical women in History Portraits, which specifically rebels against notions of performance of women in order to please men and their desire to conform to societal expectations.

Cindy Sherman’s Untitled #216 was created at a time when women were fighting to maintain their right to abortion but the gender disparity was still great. It is a caricature of the Virgin Mary based on a breastfeeding Madonna and Child by Jean Fouquet. Normally Madonna and Child paintings focus attention on Christ, but Sherman’s photograph is about Mary, with the baby barely visible. Sherman herself takes the place of Mary, and in emphasising her control as a mother over the lives of men, Sherman defines women on their own terms. In the contrast between her image and Fouquet’s painting, she creates a rebuke to the worship of works of art that are themselves representative of dated beliefs.

Jean Fouquet,Madonna of Melun, 1452, oil on panel, 37x 34 in., Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

In Poland, restrictive anti-abortion laws and sexual prejudice have been linked to the antagonism by the Catholic Church to any contravention of traditional family values rooted in their teachings. Supported by the Polish Catholic Church and the Pope’s declaration that education on ‘gender ideology’ can be dangerous, the Polish government limits access to sexual education and care and stigmatises sexual minorities and feminists, along with men and women who refuse to conform to traditional gender roles.

In Untitled #216, Cindy Sherman actively challenges such stigmatisation. In the depiction of Mary, the viewer is surprised to encounter a fake, plastic breast that is attached to Sherman’s own body. Sherman referred to this detail in her interview with Art 21: “The tit in [Untitled #216] looks like a slice of half a grapefruit stuck onto someone’s chest…But in Old Master paintings a lot of these figures’ breasts don’t even look real”. Her comment suggests that her use of caricature mocks the fact that men do not understand women nor their bodies. The fabricated theatrical effect at once subverts Mary’s sexuality and asserts that the real woman behind the image is not as she is portrayed.

The exposed breast is the defining detail in Jean Fouquet’s painting and in emphasising its artificiality, Sherman alters the focus from a worship of the Virgin’s piety to a praise of women’s reproductive and heroic power. Sherman wanted to alter the view of her as a model of the kind of mother women should aspire to be, which disempowered women. Instead, she commented on the ways in which a woman’s ability to nourish her child has been used against women to limit their freedom in society throughout history, by creating the assumption that if they do not breastfeed they are not ideal mothers. As such, the image disobeys male scripted notions of motherhood and beauty to present an independent woman who is celebrated for her power, but in a way that does not limit her agency. It is a reminder that such artworks can be a powerful tool for combating sexism and that reform from below can be as political as it is potent, fighting to bring into effect fair and positive futures.

In reflection of the developments in women’s rights, Sherman’s photographs of biblical women assert both women’s rights to their reproductive capacity and to the strength and influence they can possess to protect their communities. Following in the footsteps of other female artists and art historians of the Women’s Movement, who were commenting on the male controlled historical representation of women, Sherman implied the continued suppression of woman’s agency, which in Fouquet’s painting is pushed into the shadows. Instead of being submissive and subservient, Sherman prioritised Mary’s humanity over her holiness. She is protected from objectification and her motherhood is only a fraction of her identity, rather than completely defining her. When Sherman made the image, many women felt they could either be mothers or have a career, but not both. In challenging this, the artist asserts the possibility that women can be mothers but without it subsuming their entire purpose as individuals. Sherman’s image is therefore a powerful expression of feminist demand for recognition and social justice, without which the continuity of patriarchy would be thriving. In Poland, this same issue necessitates the renewal of feminist fights so that power can be relocated and a silence broken in which women can name and speak freely. Indeed, normativity can only be achieved through gender and sexuality discourses that target everyone.

In Polish anti-abortion discourse, pregnancy termination tends to be constructed as morally dubious and damaging to a woman’s health and emotional well-being. However, Frida Kahlo’s Henry Ford Hospital (1932) is a brutal reminder of the risks of childbirth, painted in the context of a Catholic sociocultural environment, where contraceptives were difficult to get, abortion was forbidden and deliveries were practiced despite the danger to women’s life. Kahlo was worried that pregnancy for her was too dangerous after her body had been damaged by an accident that shattered her pelvis. In this painting, Kahlo took areas of reproductive life exclusive to females like childbirth and recast them in ways that resist, even defy interpretations of ideologies that glorify motherhood and giving birth.

A hospital bed dominates the centre of the painting and lying on a bloody sheet is Kahlo’s naked body. She is represented with hair hanging loose, a large white teardrop on one of her cheeks, stomach swollen and legs bent at the knees. In one of her enlarged hands, she holds red ribbons, each with a different object suspended at the end. They carry the symbolism of tools of torture, used to convey the external side of Kahlo’s pain and which must be forcibly acknowledged by the viewer. It is a visual documentation of the bodily process she had gone through as a consequence of having ingested quinine for self-inflicted abortion, given that her doctor had declined to perform a surgical abortion. When the chemicals failed, the doctor tried to encourage her to carry the pregnancy to term but two months later Kahlo suffered a violent miscarriage. Kahlo foregrounds her own traumatic bodily process that she did not wish to experience again, portraying her grief without shame.

In anti-abortion discourse today, an attribution of personhood to the foetus strengthens the negative connotations of abortion by articulating it as a murder, but as Kahlo illustrates, this would otherwise remove the pregnant woman from the picture and overstate the foetus’ independence from the person carrying it. Rather, Kahlo is very much connected to the foetus but it is one of a fragmented assemblage of parts that is a performed dissection of her live body. She features herself at the epicentre of her pain and frustration which connects her to a narrative of heroism, sacrifice and courage. It is her pain, and nobody else’s, which refuses to be pushed to the margins of representation. As such it is a vivid representation of the tragic struggles of broken women in society, bearing burdens and painful damage caused by the society itself.

Both works by Sherman and Kahlo convey a radical perception of womanhood that challenges an emphasis on nurturing motherhood, her reproductive function and sexual purity in the very definition of what it is to be a ‘woman’. In placing woman’s agency at the front and centre, she refuses to be subject to social control. This demonstrates that the only person with the right to decide to continue or end a pregnancy is the person who is pregnant.

A more neutral or positive picture of abortion needs to be built, to compete with the negative discourse pushed by the Polish right-wing press.1 Instead, it needs to be seen in the broader context of discursive struggles about pregnancy, abortion, femininity, and individual and collective rights. Rather than view it as a stigma that is a threat to community and culture and an affront to ‘the ideals of womanhood’, women should be encouraged to speak openly about abortion as a choice that is open to all.

Inga Koralewska & Katarzyna Zielińska (2021): ‘Defending the unborn’, ‘protecting women’ and ‘preserving culture and nation’: anti-abortion discourse in the Polish right-wing press, Culture, Health & Sexuality Journal.