🤖🇪🇺 The Future of AI and Ethical Implications

A Progressive Perspective

Recently, I had the pleasure of presenting an enlightening debate on the future of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its ethical implications. The event, organised by Progressiva in collaboration with the Ettore Luccini Study Center, brought together prominent figures in the fields of AI, politics, and philosophy, including Brando Benifei, head of the Democratic Party at the European Parliament. He shared his insights on the recently approved European AI regulation, highlighting Europe’s pioneering approach to technology regulation.

Artificial intelligence is a disruptive technology that is changing the world we live in. Its implications for society are profound and complex, affecting various aspects of our lives, from work to privacy, security, and ethics. Here are some reflections from my introductory speech.

👾 The Ethical Risks of AI

Luciano Floridi, Professor of Philosophy and Ethics of Information at the University of Oxford describes the advent of AI as a digital revolution comparable to the Industrial Revolution due to the breadth and depth of changes it is causing. A McKinsey study predicts that by 2030, 30% of working hours in the United States could be automated through AI, a prospect that raises significant ethical questions. Considering that this transition is just six years away, it’s essential to address these scenarios starting from the very definition of AI.

AI, though lacking a universal definition, is generally recognised for its ability to emulate human cognitive functions such as reasoning, learning, planning, and creativity. This capability raises significant ethical issues, especially when considering the removal of the human factor in certain decision-making processes.

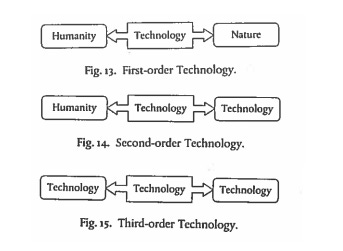

Floridi explains in his book that AI is a third-order technology. First-order technologies are those that stand between humans and nature, like an axe used to cut down a tree. Second-order technologies stand between us and another technology, such as the engine that allows us to drive a car. In the case of AI, we’re dealing with a third-order technology, one that stands between one technology and another, completely eliminating the human factor. This removal of the human element entails a series of ethical risks that are crucial to address.

AI’s Potential and Ethical Concerns

Many have spoken about the risks of AI, starting with Stephen Hawking, one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century, who stated that AI “could be either the best or the worst thing to happen to humanity.” Recently, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, which developed ChatGPT, highlighted the urgency of an ethical approach to AI development at the World Economic Forum. ChatGPT, currently the most advanced AI platform, is widely used despite being a prototype, especially in education. Regulators aren’t even attempting to ban its use, recognizing its reality and focusing instead on regulating its usage to prevent the most problematic consequences. For example, efforts are being made to ensure ChatGPT doesn’t become “cheat GPT,” making it a supportive tool for students rather than a means to cheat.

Regulation and the Role of Europe

During the debate, we extensively discussed with Brando Benifei how the European Union has taken a leading role in AI regulation, focusing particularly on privacy protection and safeguarding human dignity. This commitment reflects an increasing awareness of the importance of a regulatory framework that guides AI development towards social benefits while mitigating associated risks. In a subsequent article, I plan to summarize our discussion and explain where we stand and the future challenges that Brando and his colleagues will face to implement this regulation.

Philosophical and Socio-Economic Considerations

One significant topic is how to set rules for AI usage. Talking with a friend who works in automation at one of the Big Four consulting firms, he mentioned that the technical skills on which we’ve based much of our education over the past 50 years might become secondary, as AI could effectively replicate those skills. Instead, what AI cannot replicate are human capacities developed through a humanistic education.

The importance of a new Humanism and the challenge for progressives are critical. The progressive world is at a crossroads: the need to defend society from AI’s pitfalls versus the urgency to harness its potential for collective improvement. This requires an organic vision and a clear agenda on this topic, integrated into a broader vision of how society and the economy should be reorganized. The lack of such a vision is one of the main problems for progressive parties at both the Italian and European levels.

Progressives have been on the defensive since the 1980s, when the collapse of the Soviet Union led many to believe that there was no viable alternative to capitalism. Since then, the progressive world has largely split into two currents: those who have uncritically embraced the European project without attempting to improve it, and those who have entirely rejected this model. An example of this dichotomy is the recent movements like Mélenchon’s in France, which illustrate a broader trend among progressives to resist change and regain control over production and decision-making processes through locally centered governance.

The Need for Visionary Politics

Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams discuss this trend in their book, "Inventing the Future," a highly influential text among students and young people. They term this trend "folk politics," which emphasizes the value of localism and small-scale production and organization practices, often viewing modernity as something to resist rather than integrate.

Movements like Occupy Wall Street, anti-austerity campaigns, and numerous climate change initiatives often embody this vision, prioritizing the local and the concept of Zero Kilometers. While these principles are essential, they risk losing the ability to envision a radically new and better society—a central capability in socialist, progressive, and communist thought. "Inventing the Future" urges the progressive world to rediscover and renew this visionary capacity, moving beyond folk politics to embrace social transformation that boldly addresses the challenges of modernity.

In conclusion, the progressive world has long been on the defensive, rejecting modernity when it should be the foundation of progressivism. At Progressiva, we believe it’s time to go on the offensive, creating a new, organic vision and progressive agenda at the European level. This agenda should provide a comprehensive view of these evolving phenomena, guiding change and using it to benefit everyone, thereby creating a better society and world.

The advent of AI calls for a new Humanism, one that places humans at the centre of development and values human and philosophical capacities. Progressives face the challenge of developing an alternative societal project to neoliberalism, capable of responding to AI’s challenges and leveraging its potential for the benefit of the many, not the few. While this is a complex issue that goes beyond a single event or article, the event in Padua on February 13, 2024, contributed to this discussion, offering reflections and opening new avenues for dialogue. It’s crucial to continue this conversation to find the best solutions for a fairer and more sustainable future. AI has the potential to improve our lives, but it must be developed and used responsibly. Through a renewed Humanism that exalts human virtues and thought, we can guide AI development to contribute to building an equitable and sustainable society for all.