Responding to Climate Change in Art

Provoking us into action?

The mission of explaining the dangers of global warming to the public has always been a difficult one, yet when the existence and effects of climate change are unquantifiable and often invisible, artistic representation can bring visibility to what is unseen. By offering new ways of perceiving climate change through an appeal to the emotions, imaginations, and senses, painting helps us to envision new social realities. However, there is another side to the coin. As a representation, does art inevitably distance us from whatever problems it might address?

First, let us consider how art has contributed to our collective memory of the pre-industrial climate. In this painting, The Icebergs, 1861, Frederic Edwin Church presents to us a sublime view of the Arctic. It depicts the treacherous maritime route of the Northwest Passage which drove European exploration and inspired human awe and humility.

Frederic Edwin Church, The Icebergs, 1861

It was the danger and beauty of the unknown North that enchanted an adventure-hungry public, similarly moving artists to create resplendent views of the Arctic that has gradually crumbled over the past century as global warming wreaks havoc on the icy sea.

During the last decade, artists from all over the world have taken on climate change as a social problem, their art playing a crucial role in allowing people to rethink the role of humanity’s everyday activities in irrevocably changing the climate system. Artists such as Diane Burko have sought to appropriate and invert the sublime imagery of Church’s The Icebergs, into an apocalyptic elegy to the melancholic beauty of melting ice. Images such as Burko’s Antarctica Triptych convey an urgency by stirring in viewers a combination of positive and negative emotions.

Diane Burko, Antarctica Triptych, 2010

By portraying the beauty of the Antarctic and its demise, Burko seduces the audience as well as reminds them of the fear and overwhelming sense of tragedy unfolding before them. In Church’s nineteenth-century painting, the sublime vision of the Arctic evokes an exhilarating but fraught recognition of nature’s illimitable power over humankind. As distant viewers, we must regard ourselves as ‘safe and secure’ in order to experience the satisfaction of the sublime. However, in Burko’s imagery, the sublime is transformed into an accentuated danger or pain that presses far too closely - and is quite simply terrible.

Scientists respect and appreciate Burko’s artistic interpretation of their data and they enjoy collaborating with her. Referring to Glacier National Park, she has said:

…in the 1850’s there were 150 glaciers and now there are less than 25. While it took thousands of years for a glacier to form, it’s astonishing to see so many disappear in the last 200 years — essentially beginning at the advent of the industrial age. The severe increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, due primarily to the burning of fossil fuels, is the cause and climate science emphatically agrees that we are at a tipping point, but it is complicated…

Trekking over deep, sometimes treacherous, icy chasms to witness first-hand the rapid melting of glaciers shows what Diane Burko is willing to do to be accurate in her work. The rapid acceleration of glacial melting has serious negative impacts, such as flooding from overflow of water from the melted ice into rivers; rising sea levels; vanishing coral reefs; increased global warming; potable water shortages; shortage of fresh water for farms; food shortages; harmful impacts on animals, birds and fish; hydro electricity shortages; and more earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

As viewers, Burko urges us to look at what we stand to lose forever if we don’t do something about climate change. Yet the horrific irony is that in order to preserve the Antarctic’s sublime beauty, people in several countries would have to significantly reduce their CO2 emissions – so drastically that it cannot happen without profound lifestyle changes. In this respect, the collective denial is so powerful that the contemplation of Burko’s artwork leads us to revel in the thought of apocalypse, the fate of the earth both in our hands and somehow out of them.

James Howard Kunstler describes a first-person experience of this effect at a conference he attended. He describes someone talking about the sixth mass extinction using artist renderings, and the resulting discomfort, even horror, it produced among the audience. Yet the most interesting part of his testimony is in what happened next:

‘Personally, I was so depressed I felt like gargling with razor blades…yet a few hours later, the horror of it all was forgotten and the conference-goers reported to the next supper buffet with their appetites recharged, happy to scarf more lobster and beef medallions and guzzle more liquor, while chatting up new friends about their various hopes and dreams for the continuing story of civilized life here on good old planet Earth, which, it was assumed, had quite a ways to go before any of us needed to worry about its fate, if ever.’ (Kunstler, The Long Emergency, 2005)

Herein lies the challenge and inherent tension in climate change art too: images can not merely inspire a catharsis. The mind must be reconfigured, rather than the experience washing over us only to be promptly forgotten. In this respect, art that represents the issues and effects of climate change does not automatically have the capacity to shift awareness and provoke action. Rather, in order to foster a more active or embodied engagement with climate change, climate change needs to be reconceived as something that is not ‘out there’ (located in a global imaginary or in distant places such as the Arctic or Sub-Saharan Africa), but as something that has relevance for all cultures across all scales, and thus is something ‘in here’, entangled in contemporary practices and future possibilities. Climate change is not an entity to be observed, but rather an integral and prescient part of human culture.

Collaborative projects between artists and different groups of people may facilitate more meaningful and diverse cultural responses to climate change, moving images away from the obvious to help facilitate more present and human-centered responses and revealing the limitations of the knowledge systems through which we make sense of the world. Perhaps finding a new visual language can rely on communicating a message and providing a means or imaginative space through which to reflect upon our role as humans in a climatically changing world.

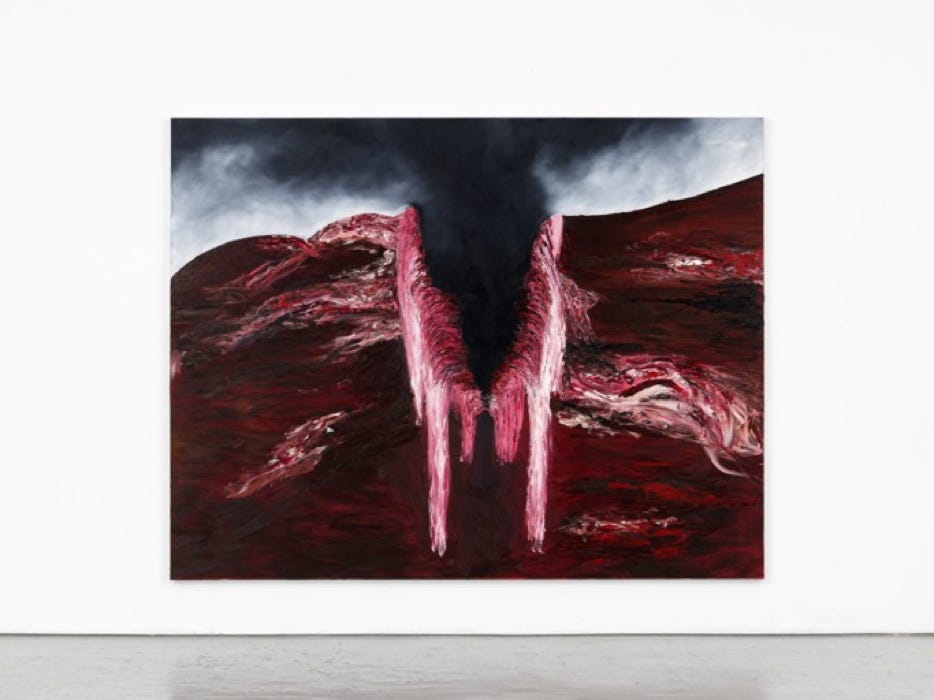

Indeed, art’s ability to move the beholder is perhaps most effective when it is not instrumental or obvious in its message, instead seeking to make us question what it means to be human. Art that entails ‘unknowing’ can stimulate questioning and produce a deeper level of engagement with the artwork. In a current exhibition at Modern Art Oxford, Anish Kapoor’s attitude of unknowing has pushed beyond conventional constraints and expectations, resulting in an output that has attracted international acclaim. Kapoor says that the paintings ‘celebrate the sensual while always knowing that decay is close’. Inviting us to consider what it means to be in this world, and to be responsible for it, one painting in particular is striking in its raw vulnerability.

Anish Kapoor, The Dark, 2021

In The Dark, the vibrant redness of human blood is commingled with the earth, which erupts beyond its boundaries in a cataclysmic event. Although it is without an exhibition label, or ‘distanced’ interpretation, the imagery leaves us in no doubt that we are intricately bound to nature and are responsible for its demise. As Kapoor states, ‘there are two ritual materials and only two. One is earth and the other is blood, and they are deeply connected to each other’. The artist compels us to unlearn what we think we know, ‘in order to intimately engage with the messy reality of our individual and universal existence’.

In this assessment of climate change art, there is the recognition that it is not always easy to reach an audience even if it is the intention of the artist or activist to do so. However, recognising the need for personal accountability and connection to causes and consequences is one important step towards finding solutions. Change in thought can only come from an understanding of how our thinking about climate change is shaped in the first place and unless our perceptual framework is questioned and transformed, the message will continue to remain lost.