HOW TO FINANCE INVESTMENTS FOR GROWTH

REDUCTIONS IN SOCIAL EXPENDITURE DO NOT APPEAR TO BE THE BEST WAY. THE GERMAN CASE

A critical political goal of most conservative European parties has been to reduce state social expenditure to keep taxes low while balancing the budget. These parties can rely on the support not only of the wealthy, who naturally oppose higher taxation, but also of many middle- and low-income earners who fear that generous social policy could reduce their income since resources are considered a given quantity to be shared according to a zero-sum-game of sorts: if somebody gets more, somebody else has to get less. This reaction is most pronounced towards immigrants, who, despite statistical evidence to the contrary, are often perceived as a net burden on society. Accordingly, social expenditure is seen as a kind of waste to be minimised and not, if fairly and properly structured, as a positive contribution to the welfare of society and, with it, also to a higher productivity of the economic system.

However, independent of how powerful the mix of support for conservative parties may be, it is not uncommon that a restrictive social policy backfires, resulting in electoral defeat. Among the most notable examples in Europe are to be considered the victory in Poland of Kaczyński’s PiS against Tusk’s PO in 2015 as well as last year‘s defeat in the Netherlands of Rutte’s VVD to the benefit of Wilders‘ populist PVV. The last case has just been be offered by the general election in the UK. To mention on purpose a non-leftist newspaper, the situation in this country is well described by Robert Shrimsley in the Financial Times on June 6th: “Stalled growth increased pressure on the public finances. And voters have noticed. Towns have not levelled up; food is not cheaper; immigration has risen; and public services have deteriorated.“

But how effectively can reductions in social expenditures, while keeping taxes constant, allow for higher state spending required by the urgent need for digital and environmental transformation, as well as the restoration of public infrastructure and services—particularly in the health and education areas—alongside a substantial increase in military spending due to a profoundly changed geopolitical situation?

It is worth examining the German case as a significant example of how far the local conservative parties have gone to stretch their arguments in support of their unwavering commitment to lower taxes and reduced social expenditure, aiming to boost economic growth through higher private investment – this despite the lower demand for consumption resulting from a shift of the income distribution that primarily benefits the wealthy. This stance of the conservative parties has remarkably remained unchanged in Germany even after the reduction of the corporate tax rate in 2008 from 25% to 15% did not generate the promised increase in investments. In fact, gross investments in plants and equipment as a ratio to GDP stagnated in Germany for a whole decade below the level shown in 2008 (28,2% of GDP), well beyond the possible depressing effects of the financial crisis in 2007-08. As we know from multiple examples in many countries, companies have used, to a large extent, the additional liquidity derived from reduced corporate taxes in the increased dividends, share buy-backs and a generally higher demand for financial assets. This is what happens if expectations from domestic investments are relatively unattractive for companies, particularly if economic growth is not promising.

Obviously, it is not easy to sell reductions in the welfare of a considerable part of the population due to a lower social expenditure of the state. Many doubt that the German Christian-Democratic Union - CDU are bringing forward sufficient arguments in favour of such a policy. Marcel Fratzscher, head of the DIW institute, has denied it: „All facts seem to contradict such a narrative (Die Zeit, 22.02.2024).“ However, this is the path that the CDU, along with its Bavarian sister party, the CSU, has taken. This is the position that the vice chairman of the Bundestag fraction and speaker for economic and social matters, Mathias Middelberg, took during the debate on the budget law on January 30th. A few weeks later, Friedrich Merz, Head of the CDU, unmistakably stated, addressing the social democrats (Tageszeitung, 23rd May 2024): “If we consider the whole budget for social expenditures as untouchable, and we are talking here about more than the half of the federal budget, then every discussion is meaningless … we can find financial resources only if savings are carried out elsewhere.”

But what can be the “facts” contradicting CDU’s narrative according to Mr Fratzscher?

First of all, the total of the state contributions (including administration costs) to the total social expenditure as a percentage of GDP had been decreasing until the Covid crisis (from 10,9% in 2011 to 10,4% in 2018) and have returned to the initial level afterwards (10,9% in 2022, according to the last available Sozialbudget). A further decrease is expected for the year 2023. As a matter of fact, Germany is far from experiencing a steep increase in social costs, as some politicians claim, strikingly making most of the time reference only to absolute figures.

Secondly, the single components of social expenditure are not expected to show in the future, despite all discussions, uncontrollable upward trends, even the most contentious of them – pensions. Although the working-age population is expected to decrease further, the latest projections (EU Aging Report 2024) show that the German pension expenditure as a ratio to GDP should increase by an unproblematic 0.8% by 2050 and by 1.2% until 2070, still significantly ending lower than its level in 2000. Actual figures confirm, as the following chart shows, that pensions have been under control and that their recent spike due to Covid has been decreasing after a peak in 2020 (2023e: 11.9%), not too far from the level at the start of the last decade. Also, contributions from the state budget into a pay-as-you-go system have hovered at around 2.6%.

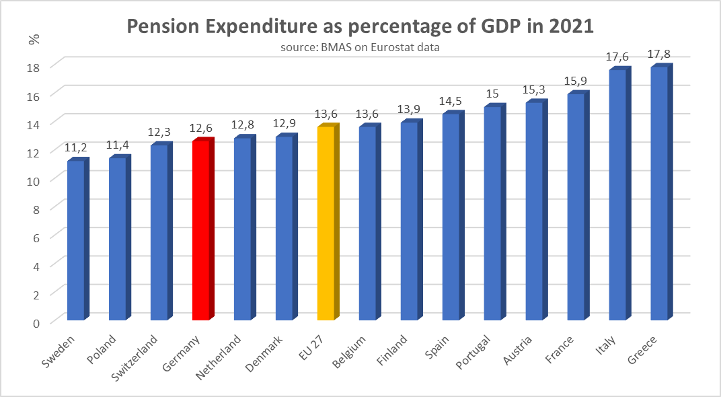

It is also worthwhile to mention that the country has a relatively large room for manoeuvring since German pensions are well below the average European level, as shown by the following chart:

Lastly, the strong effort of the German government to contain social expenditure is best demonstrated by the evolution of social expenditure at the Federal level (the “Bund” level), i.e. by the aggregates which it can directly influence. Its ratios to GDP and total Federal expenditure were in 2023 at the lowest level since the beginning of the last decade.

But what is the amount of the investment needed by the state to restore the neglected and ailing infrastructure of the country, and which should, according to the conservative parties, be made possible in the first instance by limiting the social expenditure at the charge of the state budget?

The iW (Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft) together with IMK (Institut für Makroökonomie und Konjunkturforschung) has recently gone through this exercise updating a study prepared in 2019 by H. Bardt et al. and came up with a total amount of appr. € 600 bn[i] to be allocated during a 10-year period, i.e. € 60 bn yearly (at 2024 prices).[1] It is immediately apparent that such an amount, which would i.a., not include accompanying increases in current outlays and is considered by the authors of the short study to be at the low end of an estimate, cannot realistically be funded to an appreciable extent through a reduction in the charge to the state budget for social expenditure (€ 424 bn in 2022 – source: Sozialbudget).

It is not a coincidence that the line of attack for savings in the social expenditure has had the Bürgergeld (citizen’s benefits – i.e. transfers to long-term unemployed or low-paid workers) as its main target since their beneficiaries, contrary to pensioners, are basically not among the supporters of conservative parties.

In fact, contrary to what has been often claimed[ii], Bürgergeld (previously: Hartz IV) transfers are by definition consistently below minimum salaries as they are strongly linked to inflation on the base of a basket of goods and services (end of 2023 it included approximately just a 4% improvement in real terms since 2005, the year of inception of the related law[iii]). As a matter of fact, the number of beneficiaries is presently 1 million below the situation of ten years ago, i.e. down to appr. 5.5m despite a 0.7m inflow of Ukrainian refugees in 2022, and, significantly, the charge to the state budget has been reduced from 1.8% of GDP in 2010 to 1.2% in 2023.

While being perfectible as any law or scheme, the Bürgergeld/Hartz IV shows a reasonable functioning not only regarding the unemployed in general but also refugees who have access to the benefits after 18 months from arrival in the country. A very recent study by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs shows, in particular, that the employment rate of refugees reaches 86% after eight years in the case of men (only 33% in the case of women, but also on the rise), 4% higher than the employment rate of the German men population.

Going back to the issue of the investment need in infrastructure there is no practicable way than using debt in a sustainable way and banking by the time on additional growth generated by investments and productivity improvements.

The above-mentioned iW study remarks that an extra 1.5% debt generation above the (very modest) 0.35% debt break (Schuldenbremse) necessary to finance the yearly € 60 bn investments in the framework of a special fund, as also industry associations are asking for, would still allow an appreciable reduction of the state debt well below 60% of GDP, the Maastricht limit for state indebtedness (present level in Germany: 63%).

PAR – 09.07.2024

[ii] This has gone so far that C. Linnemann, CDU’s General Secretary, based such thesis in an interview on television in 2023 on a IfW study which had to be withdrawn immediately thereafter due to faulty calculations.

[iii] To the benefit of complete information, it is to be mentioned here that partial anticipation in the formulas of the expected inflation has led in 2024 to a significant and unintended increase in the subsidies above the actual inflation rate. Due to the built-in mechanism, the excess will be absorbed starting next year. This may well justify a correction of the mechanism – definitely not its jettisoning as loudly requested by some.