Europe’s political history: the European Coal and Steel Community

“You have to know the past to understand the present.”

-Carl Sagan

While teaching a course on European economic and political history of the 20th century, I realised how little we know about the EU, and this was not only true for my students! Before teaching the subject became my profession, I was also unaware of the hidden discussions behind some of the most fundamental moments of European integration. As the single most important institution that influences – both positively and negatively – the lives of Europeans, spending a bit of time discussing its history is essential.

Ignoring the naive, story-telling veil which still covers the history of the European Union and analysing the facts is an important step towards understanding, and hopefully resolving, the modern day problems facing the Union.

The early years of European integration which are often lauded were, in fact, composed of as many failures as successes. The original notion of a political European integration project was abandoned, and in a way betrayed, in favour of an economic project, which fell kinder on the ears of European elites. These elites would, having originally been on the verge of being overthrown following WWII, succeed in consolidating their power and limiting the proposed Federal integration.

The beginning of the European Project

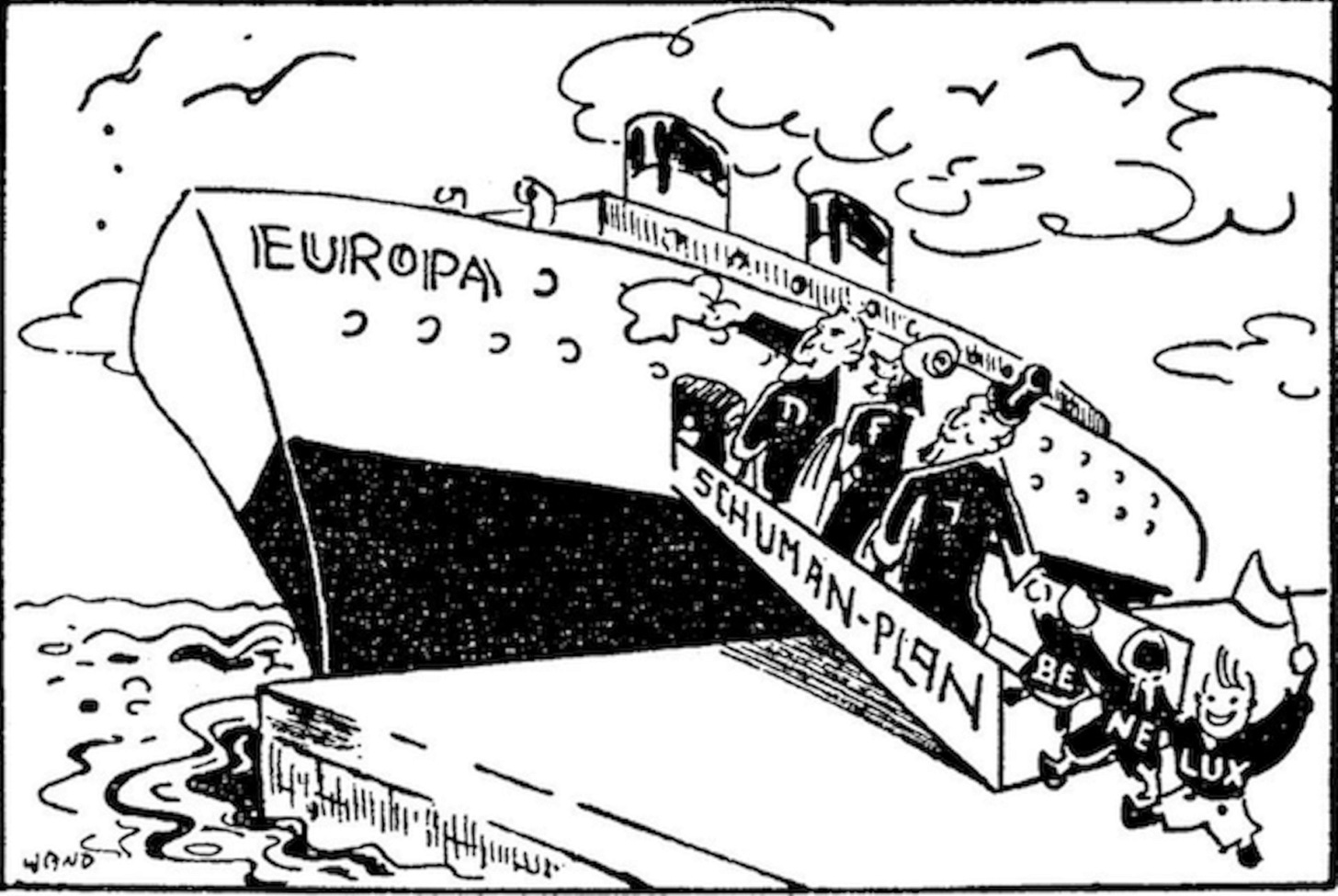

The 1952 European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was the first European supranational institution. It was a historic moment in which the six founding countries, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, decided to share and co-ordinate their production of coal and steel.

Like me, you may have learned about this at some point during your education and, also like me, you may not have paid such historical moments much attention. But have you ever wondered why the coal and steel industries were chosen as the first step? Or for that matter, why did (only) these six countries participate?

To answer these questions, we must journey back to the The Hague Congress of 1948, commonly known as the Congress of Europe because, for the first time, European integration was discussed as a genuine possibility. Two disastrous wars over the previous 35 years had caused an inevitable decline across the entire continent.

The question of how to guarantee peace was complicated by the outbreak of the Cold War. Germany and Europe were divided into two ideologically opposed blocs. In this climate, it took a lot of courage to start a congress to promote European integration. At the same time, these are the reasons that integration was seen as a priority.

At the Congress, two factions clashed from the beginning. The unionists, led by Winston Churchill, and the federalists. In essence, we can say that the Unionists wanted to maintain national governments within a possible European government, while the federalists wanted to create a true European State with a parliament and supranational powers – the United States of Europe, to use a fashionable expression at the time.

After the discussion, the Unionists got their way and only two organisations were created: the Council of Europe and the European Court of Human Rights. The Court was an important instrument in the preservation of human rights but its findings had very few political implications. The Council of Europe was a consultative body, with no real power to impose supranational laws. The question of how to proceed towards the creation of a European supranational institution remained unanswered and, according to many nations at the time, unimportant.

The European Coal and Steel Community

Proposed by the French Foreign Minister Robert Schumann, the ECSC signalled ‘a diplomatic revolution on the Continent’, shifting the balance of power and beginning the long path toward what we know today as the European Union.

It was agreed that France and West Germany would assume central roles in future integration processes. It also meant a marginalisation of the United Kingdom, which had been a main actor in continental relations until that point.

France was also able to achieve a series of goals:

An institution was created which allowed the country to take control of the process of European integration.

West Germany and France became bound economically. World War II had just finished and France and Germany had spent more than 100 years fighting each other, particularly for control of the Lorraine and Alsace border regions, where German military superiority was based. Sharing the coal and steel production meant that not only were Germany and France united economically, but it also eliminated the overwhelming arms superiority enjoyed by Germany.

France was successful in its vehement opposition to the US and British-led proposal to allow Germany to rebuild an army.

In this sense, the ECSC was a foreign policy development and as far as European integration is concerned, it was the first step because it was the least controversial. It was suggested that the ECSC be combined with the proposed European Defense Community (EDC) to create the European Political Community (EPC).

The ambitious EPC proposed the creation of a European democratic parliament which would also control a European army. Both the EPC and EDC failed in 1954 due to France’s rejection of the EPC, condemning European integration to a slow, laborious path forward. An elected parliament was finally obtained in 1979, but we are still without a European army.

The ECSC and the EEC, successes or helpful failures?

In reality, the ECSC was the best that could have been hoped for in the first 10 years of the postwar period. It is often taught as a success story along the lines of ‘making the best of a bad situation’. What they do not usually teach us at school, however, are the failures of the European integration project and the complexity of the debate around it.

Looking at the 1950s, we can see how the only institutions that European politicians were able to create were economic institutions, based around the notion that economic integration had to be the priority. Political and social integration were secondary goals, to be attained in the future if the mood struck.

In a groundbreaking book published in 1992, Alan Milward supported the idea that the history of European integration was not a history of selfless European founding fathers who renounced national sovereignty in the name of European ideals. Instead, he affirmed that the European elites were forced down the European path due to a lack of credibility in the aftermath of World War II. He elaborated further, saying that thanks to the European institutions, these discredited elites were able to maintain power and the only concessions they made were what was necessary to survive.

When studying history, we learn that the truth is never black and white. The history of the EU is not only a story of success, it is also a story of several failures; failures which influenced the path to Europe's integration, which was opposed by many in the national ruling classes.

It is also the story of two different projects. One economic – the creation of a common market which has continued to grow at a constant pace – and one political – the creation of a European political supranational authority, which was primarily a failure throughout the 1950s, and is not yet completed today.

The European Union is by no means perfect, but it has come on leaps and bounds since its inception as the ECSC all those years ago. Unless we continue to explore and understand the true historical context of the modern-day issues facing the EU, we may never overcome these problems.