Australia has voted for climate action, and is class politics dead?

Voting in the 2022 election has cut across socio-economic issues and disrupted the two-party system

The leader of Australia’s social democratic Labor Party will form government following Saturday’s election, unseating the conservative Liberal/National Party Coalition government after nine years of rule. This is only the fourth time since the Second World War that the Labor Party has won from opposition, and they have done so with their lowest primary vote (voters placing them first in the preferential voting system) since 1919 – just 33 per cent at current estimates. Support for both far right parties and the leftist environmental party, the Greens, has grown, but a large number of moderate independent candidates have also been elected, campaigning on climate action and gender equality. The 2022 election has disrupted the effective two-party system that has existed for the last century.

There are a number reasons why this election is relevant and interesting for a European audience. Firstly, the Labor Party has campaigned on making Australia a renewable energy superpower by, among other things, investing in the production of materials for renewable technologies. The large number of votes for the Greens and the so-called ‘teal’ (moderate, environmentalist) independents gives the new government a mandate for action on climate change, not least because they may have to work with the independents or Greens in the House of Representatives (the lower house), and will certainly need support from the Greens in the Senate to pass legislation. Australia is one of the world’s largest exporters of coal, so this shift in policy matters for Europe and for the world. Concerned not to alienate mining workers, the Labor Party has said it will still support new coal projects if they ‘stack up environmentally’, but the Greens are committed to phasing out mining.

Secondly, votes for both the ‘teal’ independents and the far right suggest that ‘second dimension’ politics played a big role in how Australians decided to cast their vote. That is, people based their votes not only on their class identity or socio-economic concerns, but on cross-cutting issues like climate change, gender equality, and immigration, which divide voters with more traditional values and nationalist views from those with more progressive and environmentalist tendencies.

Climate change was the most important issue for voters, and votes for climate action have come from across the socio-economic spectrum. The Greens have likely returned their highest proportion of primary votes ever, and won at least one additional seat in parliament. At the same time, independents campaigning on climate change and gender equality have attracted votes from a wide group of Australians who have perhaps viewed the Greens as too far left economically. Most of these independents are women, and some were former Liberal Party members or come from well-known Liberal families. They were funded by grass-roots contributions and the lobby group Climate 200. By finishing first or second on first preferences, independents have been able to win seats from moderate Liberal candidates in both wealthy inner-city seats and country Victoria, and from the Labor Party in western Sydney.

Like in Europe, the vote for the far right has continued to grow in Australia, but this hasn’t resulted in increased parliamentary power for these parties. Pauline Hanson’s One Nation received 4.9 per cent of the primary vote on current estimates, while the United Australia Party received an estimated 4.2 per cent. These numbers have grown from 3.1 and 3.4 per cent respectively in 2019, and just 1.3 per cent and less than 1 per cent respectively in 2016. No far right parties have won seats in the House of Representatives, where Australia has a single transferable voting system and seats are allocated to the candidate in each electorate with a majority of votes after voter preferences are distributed from the candidates who received fewer primary votes. The far right party, One Nation, retains its single seat in the Senate, where seats are allocated on a proportional basis and senators sit for six years.

As a result of the election, the defeated Liberal/National Party Coalition has been transformed. Although technically two parties, the conservative Liberals and agrarian Nationals have worked together for so long that they are effectively a single party. But while the rural/agrarian Nationals have retained all of their seats in country New South Wales and Victoria, the Liberals have lost many seats across the country. In particular, many of the moderate Liberals have left the parliament, leaving the more conservative right wing of the party with the balance of power in the caucus. With wealthy inner-city voters abandoning the party for the ‘teals’, will time in opposition lead the L/NP to address its poor record on gender inequality and formulate a more appealing policy on climate action? Perhaps more likely, Australia’s centre-right alliance may shift further right, and seek to compete with the far right in the suburbs on other second dimension issues like immigration.

The rise of second dimension politics is a global phenomenon, and while it doesn’t quite spell the end for class politics, even in two-party systems like Australia the electoral environment is being transformed.

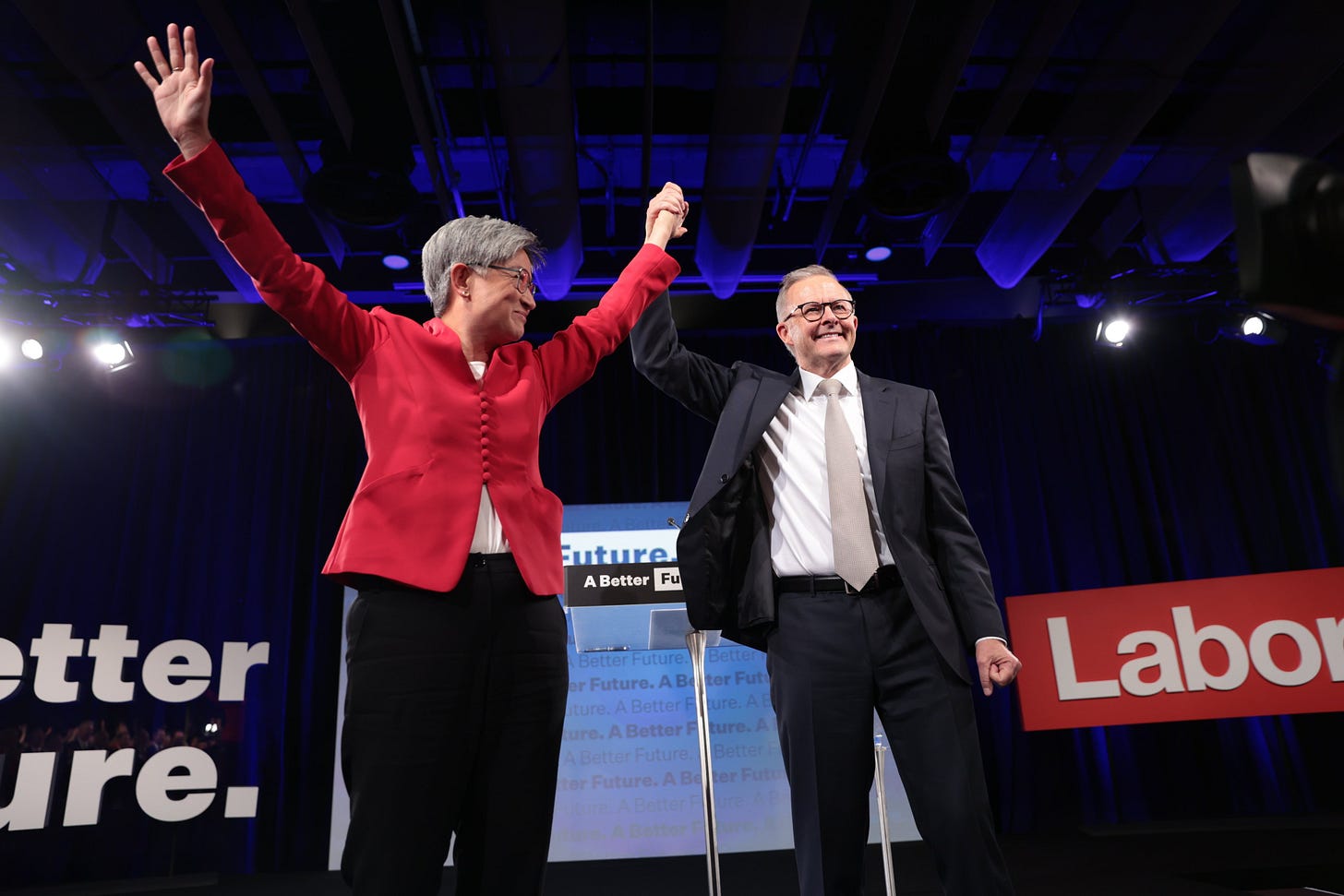

With millions of early votes and postal votes yet to be counted, it remains unclear whether Labor will govern alone – in a majority or minority government, or in coalition with or support from the Greens or independents. What is clear is that Australian politics has changed dramatically, and so too may the country. Australia’s new prime minister Anthony Albanese grew up in public housing in Sydney’s inner west and opened his victory speech with a commitment to the Uluru Statement from the Heart, promising a referendum to change the constitution to introduce a First Nations Voice to Parliament. Labor’s vision for a better future for all Australians includes universal child care subsidies, a higher quality aged care sector, a government anti-corruption commission, and – finally! – action on climate change.

Class politics is not dead. The Labor Party - which secured a slim majority - did so on a coalition of its more traditional (working class) base and the middle class (many of whom also voted independent and Greens). Key components of the Labor were support for an increase in the minimum wage and the notion that government has a role in supporting working people. Labor were assisted on this latter point by the deliberate neglect and failure of the former conservative government to provide effective services during Covid and a range of fire / flooding emergencies, and cost of living pressures that escalated during the course of the election campaign. Perhaps because of this, Labor were able to avoid / ignore the attempts to engage in Culture Wars that the Liberal Conservatives threw up. It is true that climate change, gender and government integrity issues also played key roles - especially with the middle class voters who voted Greens or independent but there was also a sharp focus on material concerns. What is clear is that for the working class who voted Labor or even Greens in some instances, did so on the basis of traditional class based material (economic) concerns. The new Labor government has inherited significant challenges in energy, the care economy sector, and the economy generally (inflation, low wages etc). The pressure will be on to move away from the neoliberal market based solutions that have caused damaged over the past 20 years. Failure to do could well risk a disintegration of the cross coalition that Labor secured in winning the election. In short, Class is not dead. If anything, the fragmentation of the vote across parties & candidates reflects the search by class actors to find the representation that bests addresses their interests.